Last updated on 2025/05/01

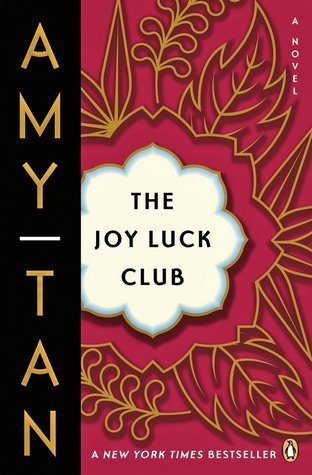

The Joy Luck Club Summary

Amy Tan

Bridging Generations Through Stories and Culture.

Last updated on 2025/05/01

The Joy Luck Club Summary

Amy Tan

Bridging Generations Through Stories and Culture.

Description

How many pages in The Joy Luck Club?

352 pages

What is the release date for The Joy Luck Club?

In Amy Tan's poignant novel, "The Joy Luck Club," the intricate tapestry of generational conflict and cultural identity unfolds through the lives of four Chinese American daughters and their immigrant mothers, whose past experiences shape their present realities. As the mothers share haunting memories of their struggles in China, the daughters wrestle with the expectations and traditions imposed upon them in America, ultimately leading to a profound exploration of love, sacrifice, and the bridges between their worlds. Through rich storytelling, Tan invites readers into a dialogue about the complexities of familial bonds and the universal quest for self-discovery, making it a compelling read for anyone who has ever felt the weight of both heritage and aspiration.

Author Amy Tan

Amy Tan is a renowned American author best known for her compelling narratives that explore the complexities of mother-daughter relationships and the immigrant experience. Born on February 19, 1952, in Oakland, California, to Chinese immigrant parents, Tan's upbringing heavily influences her writing, reflecting the struggles of cultural identity and generational divide. She gained significant acclaim with her debut novel, "The Joy Luck Club," published in 1989, which intertwines the stories of four Chinese American daughters and their immigrant mothers, articulating the nuances of their cultural heritage and personal journeys. Tan's work is characterized by its rich, lyrical prose and profound emotional depth, earning her a place as one of the leading voices in contemporary literature.

The Joy Luck Club Summary |Free PDF Download

The Joy Luck Club

Chapter 1 | Feathers From a Thousand LI Away

In the first chapter of "The Joy Luck Club," we meet an old woman reflecting on her journey from Shanghai to America, marked by a poignant memory of a swan she once bought. The vendor had claimed the swan was transformed from a duck aspiring to be something greater, symbolizing hope and beauty. As she traveled across the vast ocean, she envisioned a better life for her future daughter—a life free from judgments based on the trivialities of her husband's whims. She dreamed of empowering her daughter with eloquence and resilience, believing that in America, her daughter would thrive without sorrow. However, upon her arrival in America, the woman faced harsh realities as immigration officials separated her from her beloved swan. Left with only a single feather, she became overwhelmed by the bureaucratic demands, causing her to lose sight of her dreams and the reasons for her journey. Years passed, and she became a mother to a daughter who grew up in a vastly different world, speaking only English and consuming material comforts, like Coca-Cola, rather than dealing with deep emotions. The old woman clings to the single swan feather, longing to share its significance and the depth of her intentions with her daughter. She hopes to convey that this seemingly worthless feather carries her dreams and sacrifices from afar. Ultimately, this chapter highlights themes of cultural displacement, the complexities of mother-daughter relationships, and the struggle to communicate deep-seated feelings across generational and cultural divides. Through vivid imagery and rich symbolism, we see the old woman's hope for her daughter colliding with the realities of their contrasting lives.

Chapter 2 | Jing-Mei Woo: The Joy Luck Club

In Chapter 2 of "The Joy Luck Club," we meet Jing-Mei Woo, who reflects on her mother, Suyuan, who recently passed away. Jing-Mei is asked by her father to take her mother's place at the Joy Luck Club, a group of Chinese American women who gather to play mah jong and share their stories. This request brings sadness, as Jing-Mei struggles with feelings of inadequacy and the daunting task of stepping into her mother's shoes. Suyuan's life is explored through Jing-Mei's memories, revealing her journey from China to San Francisco. She recounts her mother's pride in cooking and her determination to support her friends after leaving a war-torn homeland. Suyuan formed the Joy Luck Club as a way to cope with the struggles faced by Chinese immigrants by gathering women to raise their spirits and share their hopes, even amid difficulties. This club provided a means to celebrate small joys through food, laughter, and mah jong — a game that offers both camaraderie and a sense of community. Jing-Mei's narrative is interspersed with flashbacks to Suyuan's past in Kweilin during the war, where she dreamed of a safe, beautiful life that ultimately turned into a nightmare. Suyuan's determination to survive and maintain hope for her family shines through, suggesting themes of resilience and the cultural legacies passed between mothers and daughters. At the Joy Luck Club meeting, Jing-Mei feels out of place among her mother's friends, who reminisce about Suyuan and share their own stories. Yet, it becomes apparent that they see reflections of their own daughters in Jing-Mei's struggle to connect with her heritage. Auntie Ying reveals that Suyuan sought to find her long-lost daughters in China, a revelation that deeply impacts Jing-Mei and highlights the complexities of identity, family, and the burden of unfulfilled dreams. As Jing-Mei prepares to relay her mother's legacy to her sisters, she grapples with her own feelings of disconnection. The chapter captures the weight of generational differences, cultural expectations, and the enduring bonds of family, packing a powerful emotional punch as it explores themes of memory, loss, and the journey of understanding oneself through the stories of one's ancestors. Through the Joy Luck Club, Jing-Mei begins to comprehend the richness of her mother's life and the joys and sorrows that shaped her identity, leading toward a promise to honor her legacy.

Chapter 3 | An-Mei Hsu: Scar

In Chapter 3 of "The Joy Luck Club" by Amy Tan, we dive into An-Mei Hsu's poignant childhood memories, shaped by her stern grandmother, Popo, who instilled a haunting view of their family's past. An-Mei's mother is a forbidden topic, considered a ghost by Popo—a woman whose memory is filled with shame for abandoning her family. Living in her uncle and auntie's house in Ningpo, An-Mei navigates a home filled with fear and strict expectations. Popo frightens her with tales of disobedient girls facing dire consequences, emphasizing the importance of respect for ancestors and family legacy. As Popo's health declines, An-Mei's fear deepens. Popo's ailing condition serves as a backdrop for greater revelations about lineage and familial duty. An-Mei's mother unexpectedly returns, creating a rush of emotions as An-Mei grapples with her conflicted feelings of longing and resentment. Upon seeing her mother, An-Mei recognizes her own features in the woman she has only heard about but never known. Her mother's arrival ignites memories of a traumatic past, particularly the night of a painful injury from a soup pot—an event that left a scar not just on her neck but on her heart, a symbol of her mother's absence. The chapter's climax unfolds as An-Mei witnesses her mother’s desperate attempt to save Popo by sacrificing part of herself, emphasizing the intricate bond of maternal love that transcends pain and sorrow. This act of selflessness reveals how deeply rooted the connection between mothers and daughters can be, regardless of past grievances. An-Mei begins to understand that love, sacrifice, and familial loyalty intertwine in complex ways—pain can bond generations more than it separates them. Ultimately, An-Mei learns that true honor and respect are embodied in the deepest forms of love, such as her mother’s act of cutting her own flesh for a healing broth. The theme of memory versus loss resonates through An-Mei's realization of her own identity, shaped by both her mother’s struggles and the burdens of their heritage. This chapter captures the essence of intergenerational relationships, the heavy weight of expectations, and the beautiful yet painful connections that define womanhood in An-Mei’s life.

Key Point: The complexity of maternal love and sacrifice shapes our identity.

Critical Interpretation: An-Mei's journey reveals how the sacrifices made by our mothers, even in pain, nurture our identities and connect us to our roots. This powerful bond encourages you to appreciate the struggles within your family, recognizing that love often comes intertwined with sacrifice. Understanding this can inspire you to embrace both your heritage and the lessons learned from past grievances, reminding you that through acknowledging pain, you can foster resilience and a deeper appreciation for familial connections.

Chapter 4 | Lindo Jong: The Red Candle

In Chapter 4 of "The Joy Luck Club" by Amy Tan, we dive into the life story of Lindo Jong, who reflects on the sacrifices she made to uphold her family's promises. Lindo expresses concern about the modern view that promises are easily broken, contrasting it with her own upbringing where promises held deep significance. She shares her early memories of being betrothed at a young age to Tyan-yu, a boy who was just a baby at the time. This arrangement was orchestrated by a matchmaker, who saw Lindo as valuable due to her looks and potential future contributions to the Huang family. As Lindo grows up, her life is marked by the realization that she is expected to fulfill her role as a dutiful bride for Tyan-yu's family. Her childhood home and family gradually become reminders of a life that no longer belongs to her, as her parents seem to prepare her for a future she cannot escape. Lindo recounts her initial impressions of Tyan-yu, describing him more as a troublesome relative than a romantic interest. However, her life takes a dramatic turn after a devastating flood forces her family to move away, separating her from her childhood. At the Huangs’ house, Lindo learns what it means to be an obedient wife under Huang Taitai's strict guidance. She rigidly adapts to the expectations placed on her, even finding some fleeting comfort in fulfilling her domestic duties, hoping to please her in-laws. As she reaches her sixteenth birthday, the pressure intensifies for her to bear children, especially with the ongoing threat of Japanese invasion looming over their lives. On her wedding day, Lindo reflects on the disillusionment of the event, as fewer guests arrive than expected due to the war’s impact. Ultimately, as she marries Tyan-yu, she feels a sense of betrayal toward her own identity as she is swaddled in the red scarf of traditional wedding customs. Despite facing a seemingly predetermined life of oppression, Lindo's inner strength begins to surface. When faced with the obligation of consummating her marriage, Lindo realizes she must navigate this oppressive environment carefully. Initially, Tyan-yu demonstrates little interest in her, which frustrates his mother deeply. However, Lindo quietly begins to adapt to Tyan-yu's timid nature, feeling less threatened over time. As months pass without any children, tension escalates between Lindo and Huang Taitai, who blames her for their inability to conceive. A turning point occurs when Lindo devises a clever plan. She pretends to have prophetic dreams that predict disaster for the marriage, which ultimately leads the family to believe it is best to annul the marriage due to supposed signs from their ancestors. In the end, Lindo manages to reclaim her autonomy and escape her stifling marriage without dishonoring her family's promise. She transitions to a new life, moving to America with a sense of independence and purpose, finding value in herself and her genuine identity beyond societal expectations. Throughout this chapter, key themes include the burdens of familial duty, the struggle for self-identity, and the resilience of the human spirit. Lindo's journey illustrates the complexity of cultural expectations and the struggle between individual desires and sacrifices made for love and family legacy.

Key Point: The importance of keeping promises under challenging circumstances

Critical Interpretation: Reflecting on Lindo Jong's journey in Chapter 4, you may realize how crucial it is to maintain your commitments even when faced with adversity. Lindo's ability to uphold her family's promises while also seeking her own identity inspires you to balance your obligations with your personal aspirations. It serves as a reminder that true strength lies in the capacity to honor your word, yet also to find pathways to personal freedom and self-expression, encouraging you to navigate life's challenges with resilience and integrity.

Chapter 5 | Ying-Ying St. Clair: The Moon Lady

In Chapter 5 of "The Joy Luck Club,” titled "Ying-Ying St. Clair: The Moon Lady," we delve into Ying-Ying's reflections on her life and her relationship with her daughter. Ying-Ying feels invisible, consumed by the demands of her current life and yearning for a connection with her daughter, who is caught up in her own busy world. The chapter unfolds through a nostalgic flashback to Ying-Ying's childhood during the hot autumn days of 1918 in Wushi, China, when she eagerly awaited the Moon Festival. As a young girl, Ying-Ying is excited about the festival and the opportunity to see the Moon Lady, Chang-o, who could grant secret wishes. Her amah, or nursemaid, prepares her for the festivities with traditional clothing and lessons about proper behavior, emphasizing the importance of silent submission for girls. This teaching reflects a broader theme of cultural expectations surrounding femininity and the sacrifices involved in fulfilling those roles. Ying-Ying’s family gathers to celebrate the Moon Festival, filled with food, laughter, and the company of relatives. However, as the day progresses, Ying-Ying becomes increasingly restless. She chases a dragonfly and plays with her half-sisters but feels a sense of longing as she yearns for freedom and expression. The adults around her, engrossed in their conversations, seem oblivious to her desires. When they finally reach the lake on rented boats, Ying-Ying's anticipation builds. However, the day takes a fateful turn when she inadvertently falls into the water after witnessing the Moon Lady's performance. As she struggles in the lake, she feels isolated and powerless, revealing her internal conflict between her childhood innocence and the harsh realities of life. The Moon Lady's tale of loss and longing resonates with Ying-Ying, who identifies with her plight. The Moon Lady laments the sacrifices made for duty and the yearning for connection, themes that echo throughout Ying-Ying's own life. In a moment of desperation, Ying-Ying runs forward to voice her own secret wish, but time slips away, and her desire remains unexpressed. Despite being rescued, the experience changes Ying-Ying. The chapter closes with her reflection on the wish she made long ago, a wish for connection and to be truly found. The intertwining of personal desire and cultural expectation, along with themes of invisibility and the longing for authentic relationships, underscores Ying-Ying’s journey and sets the stage for the complexities of her relationship with her daughter as they both navigate their identities across generations.

Chapter 6 | Waverly Jong: Rules of the Game

In Chapter 6 of "The Joy Luck Club," titled "Rules of the Game," Waverly Jong reflects on her childhood in San Francisco's Chinatown, where her mother instilled in her the concept of "invisible strength." This idea becomes a metaphor for both survival and strategy, particularly in the game of chess. Waverly’s love for chess begins when an old set, albeit incomplete, becomes her brothers' new focus. Initially yearning to join them, Waverly offers her Life Savers to trade for a chance to play. As she learns the rules from her brothers, she quickly realizes that chess embodies life lessons about power, strategy, and the importance of keeping secrets. Waverly's introduction to the game deepens when she meets Lau Po, an older man who becomes her mentor. Under his guidance, she evolves not just as a player but also as a thinker, learning intricate strategies and proper chess etiquette. Waverly's talent blossoms, leading her to win local tournaments and gain recognition. Her success attracts attention, including that of her proud mother, who celebrates her victories but also imposes high expectations, urging her to win more and lose less. Conflict arises as Waverly grapples with her identity and her mother's proud assertiveness, which she finds stifling. This tension peaks during a market outing when Waverly expresses embarrassment about her mother’s boasting, leading to a dramatic confrontation where she runs away in anger. Alone in the city, she experiences a sense of loss that parallels the chessboard's solitary battles she frequently envisions. The chapter closes with Waverly feeling the pressure of competing against her mother’s expectations and the self-imposed weight of her ambitions, caught between striving for success and seeking autonomy. Themes of identity, cultural expectations, and the struggles of a young girl balancing her ambitions against family loyalty emerge vividly in Waverly’s journey. Her victories on the chessboard mirror her inner battles, as she seeks to carve out her own path while navigating the complexities of cultural pride and personal aspirations.

Chapter 7 | Lena St. Clair: The Voice from the Wall

In Chapter 7 of "The Joy Luck Club," titled "The Voice from the Wall," we delve into the life of Lena St. Clair, who shares vivid memories from her childhood that reveal the deep complexities of her family dynamics, particularly her relationship with her mother, and the ghosts of their pasts. Lena reflects on a dark story told by her mother about her great-grandfather, who cruelly sentenced a beggar to death, only to be haunted by this man's ghost. This story symbolizes the fear and trauma that linger within their family, foreshadowing themes of guilt, loss, and the weight of unspoken terrors. As a child, Lena is acutely aware of the shadows that lurk in their household, particularly the emotional struggles that seem to consume her mother. She recalls her mother barricading a basement door to keep a “bad man” trapped within, illustrating an early awareness of her mother’s protective instincts intertwined with fear. Lena's unique perspective, influenced by her Chinese heritage, allows her to perceive dangers that others cannot, and this adds layers to her childhood experiences, which are marked by haunting thoughts and an imaginative yet troubled inner world. As the family moves to a new apartment in San Francisco, Lena’s mother struggles with the change. Her acute anxieties lead her to obsessively rearrange furniture, believing that their home’s imbalance might invite misfortune. This behavior hints at the psychological toll that her past experiences have taken on her, especially after the tragic death of her baby, which devastates her. Lena's observations of her mother's mental state reveal the generational trauma and the invisible emotional scars passed down from their ancestors. Throughout the chapter, Lena hears the raucous arguments next door, witnessing the chaotic life of the Sorci family. The violent echoes of their domestic disputes contrast sharply with her own family’s silent suffering. One night, when Lena befriends Teresa, the girl from next door, she learns that their experiences, though seemingly different, are intertwined by the common thread of familial strife. Teresa's nonchalant attitude toward her own turbulent life opens Lena’s eyes to the notion that love and pain can coexist in a complicated yet somehow nurturing way. As Lena navigates these turbulent family dynamics, she contemplates the idea of witnessing the worst possible fates through the walls that separate their lives. The chapter closes on a hopeful note, as Lena envisions a profound connection—a mother understanding the depths of pain and emerging from it to embrace life again, despite the chaos surrounding them. The narrative culminates in Lena realizing that the cycle of suffering and healing is a part of life, instilling a sense of hope that perhaps one day her mother will also find freedom from her haunting memories. The themes of trauma, familial bonds, and the search for identity resonate throughout Lena’s storytelling, making this chapter a poignant exploration of the ongoing negotiation between past and present.

Chapter 8 | Rose Hsu Jordan: Half and Half

In Chapter 8 of "The Joy Luck Club," titled "Half and Half," we delve into Rose Hsu Jordan's bittersweet recollection of her relationship with her husband Ted and her mother, as well as the devastating loss of her younger brother, Bing. The chapter opens with Rose reflecting on her mother's lost faith, symbolized by a neglected Bible used to balance a table. This image serves as a metaphor for Rose's own balancing act within her tumultuous marriage and the strained relationship with her mother, who harbors traditional expectations. Rose grapples with the news of her impending divorce from Ted, a decision she dreads sharing with her mother, knowing her response will be one of disbelief and insistence to "save it." Rose recalls the early days of her romance with Ted, characterized by excitement and rebellion against her mother’s expectations. Their differing backgrounds — Rose's strict Chinese upbringing contrasted with Ted's American upbringing — became a source of conflict, though she was enamored by Ted’s confidence and decisiveness. As their relationship evolves, Ted grows more authoritative, making decisions and expecting Rose to follow his lead. When Ted suffers a malpractice lawsuit, his confidence shifts, and he begins to put pressure on Rose to make decisions. This dynamic ultimately reveals cracks in their relationship, as he grows increasingly frustrated with her indecisiveness, leading to the emotional fallout that culminates in divorce. The narrative transitions dramatically to the past when the family embarks on a beach trip, a day filled with innocence and joy that quickly morphs into tragedy when Bing, Rose’s younger brother, drowns. The event shatters the family’s illusion of control and balance, cementing the theme of fate versus individual agency. Rose reflects on her childhood responsibility for Bing's safety, burdened by guilt for not being able to prevent the accident. In the wake of Bing's loss, Rose's mother displays unwavering faith, using superstitions and prayers to try to cope with their grief. Her desperate attempts to reclaim Bing serve as a poignant counterbalance to Rose’s loss of faith and control in her marriage. Through her mother’s actions, Rose learns about the complexities of faith, fate, and the necessity of personal agency. Ultimately, Rose contemplates how fate intertwines with one's expectations and attentiveness. The chapter ends with Rose finding the Bible and contemplating her mother’s longing for what was lost, relating this to her own struggles in love and life. She recognizes the pain of losing Bing symbolizes not only familial love but also the deep-seated fears in her marriage, signaling a pivotal moment of self-awareness and understanding. The weight of her family’s history and her mother’s teachings resonate profoundly, urging Rose to confront her past choices and the resulting consequences in her life.

Key Point: The necessity of personal agency in the face of fate

Critical Interpretation: In Chapter 8 of 'The Joy Luck Club,' Rose Hsu Jordan's journey reveals that while we may face circumstances beyond our control, the need for personal agency remains crucial. You may find yourself caught in situations that seem dictated by fate, similar to Rose's struggles with her marriage and family tragedy. This chapter inspires you to embrace your ability to make choices, even when confronted with loss and uncertainty. By acknowledging your power to take action, you allow yourself to navigate life's challenges authentically and redefine your path, shaping your destiny rather than letting it shape you.

Chapter 9 | Jing-Mei Woo: Two Kinds

In Chapter 9 of "The Joy Luck Club," titled "Two Kinds," we delve into the complex relationship between Jing-Mei Woo and her mother. Jing-Mei's mother, a Chinese immigrant, harbors grand aspirations for her daughter, believing that in America, anyone can achieve greatness. She tries to mold Jing-Mei into a prodigy, initially envisioning her as a mini Shirley Temple, complete with beauty training and performances. However, Jing-Mei’s journey to meet her mother’s expectations becomes increasingly fraught with conflict. The mother's ambitious plans lead to a series of tests designed to showcase Jing-Mei's talents. From memorizing facts to performing physical feats, Jing-Mei struggles to live up to her mother's relentless hopes, which only deepens her sense of inadequacy. Each failed attempt to shine as a prodigy chips away at Jing-Mei's self-esteem and ignites her rebellious spirit. She recognizes an angry, willful part of herself that resists her mother’s demands, leading her to perform poorly as a form of defiance. The pivotal moment arrives when Jing-Mei is pressured to participate in a piano recital. Her mother, despite her previous failures as a performer, insists that she can be a success if she tries hard enough. However, during the performance, Jing-Mei falters, hitting wrong notes while feeling overwhelmed by the expectations resting on her shoulders. The audience’s reaction is muted, and she leaves the stage crushed, profoundly sensing her mother’s disappointment. After the recital, their dynamic shifts. For years, Jing-Mei operates under the shadow of her mother’s aspirations, asserting her identity by rebelling against them. This rebellion is marked by a fierce argument where Jing-Mei lashes out, expressing her deep-seated frustrations and inadvertently touching on her mother’s painful past—the loss of her twin daughters in China. This moment of honesty leads to a quiet shift; Jing-Mei’s mother stops pushing her to pursue music altogether, closing the lid on both the piano and her dreams for Jing-Mei. Years later, Jing-Mei's mother surprises her by offering the piano as a gift for her thirtieth birthday. This gesture signifies forgiveness and a relinquishing of dreams once held too tightly. While Jing-Mei has long been disengaged from music, the piano becomes a symbol of their complicated relationship. After her mother’s death, Jing-Mei reconnects with the piano, reflecting on her mother’s enduring belief in her potential. As she plays pieces titled “Pleading Child” and “Perfectly Contented,” she recognizes that they are two sides of the same coin, representing her own life’s complexities—struggles against expectations and the quest for self-acceptance. Through Jing-Mei’s narrative, the chapter explores significant themes such as identity, ambition, and the generational conflict between immigrant parents and their children. Ultimately, it’s a poignant story of understanding and reconciling to one's heritage and familial expectations.

Key Point: The struggle for self-identity amidst familial expectations

Critical Interpretation: In your life, you may often feel the weight of expectations from those you love, much like Jing-Mei Woo felt from her mother. This chapter teaches you the importance of carving out your own identity, even when it clashes with the aspirations of your loved ones. It inspires you to embrace your true self, acknowledging that personal fulfillment often comes from defying imposed roles. By understanding your own desires and being open to the complexities of your relationships, you can find peace and acceptance, demonstrating that it’s okay to redefine success on your own terms.

Chapter 10 | Lena St. Clair: Rice Husband

In Chapter 10 of "The Joy Luck Club" by Amy Tan, we delve into Lena St. Clair's complex relationship with her mother and her husband, Harold. Lena reflects on her mother's uncanny ability to foresee bad things in their lives, illustrating a deep cultural belief that events are interconnected, as symbolized by the saying "If the lips are gone, the teeth will be cold." This sense of impending doom becomes a thread woven throughout Lena's memories, shaped by various experiences in her upbringing, including tragedies like the death of her father. The narrative explores Lena and Harold's strained marriage, contrasting their lives as they navigate the challenges of their professional careers and household dynamics. Lena is acutely aware of her mother's critical eye; during a visit to their home, her mother finds fault in their renovated barn, pointing out every flaw that makes Lena uncomfortable. While Lena tries to defend their choices, she secretly enjoys seeing Harold squirm under her mother's scrutiny, which symbolizes her inner conflict between loyalty to her mother and her partner. Their relationship dynamics are further complicated by financial arrangements; they have a detailed system for sharing expenses, which Lena increasingly finds burdensome. This meticulous accounting reflects deeper issues of power and equality within their marriage. Harold is the more dominant partner, making significantly more money and deciding the aesthetic of their home, which is minimalistic and devoid of Lena's personal touches. Lena recalls a childhood memory where her mother warned her about her future husband based on her eating habits—an anecdote that illustrates the pressures and fears Lena feels about her destiny, marriage, and self-worth. As she grapples with feelings of insecurity, her frustration bubbles to the surface during an argument with Harold, culminating in emotional turmoil that leaves her feeling lost. The chapter takes a poignant turn when Lena's mother accidentally breaks a vase in their home, symbolizing the fragility of their interconnected lives and relationships. Lena's acknowledgment that she foresaw this incident adds weight to her internal tension about the consequences of passivity and the fear of acting against her mother's predictions. Lena's emotional journey emphasizes themes of cultural expectations, generational conflict, and the struggle for identity within familial and romantic relationships. As Lena confronts her discontent and desire for a deeper connection, readers are left pondering the complexities of love, obligation, and the fight for agency in a world defined by the relationships we uphold.

Chapter 11 | Waverly Jong: Four Directions

In Chapter 11 of "The Joy Luck Club," titled "Four Directions," Waverly Jong takes her mother, Lindo, to lunch at a Chinese restaurant, hoping to lift her spirits. However, their outing quickly turns into a disaster as Lindo critiques Waverly's new haircut and the overall dining experience. Their personalities clash profoundly; Waverly, sensitive and eager to please, finds herself at odds with Lindo's blunt and critical nature. Despite Waverly's intentions to share her exciting news about her engagement to Rich Schields, the moment never arises amidst the tension. The relationship dynamics between Waverly and her mother are explored deeply. Lindo’s abrasive honesty stems from her upbringing, revealing a generational clash. Waverly, born under the sign of the Rabbit, is sensitive to criticism, while Lindo, a Horse, is strong-headed and forthright. This contrast fuels Waverly’s insecurities and fears about how her mother will react to Rich—her fiancé who is not only non-Chinese but also younger than her. While at her apartment, Waverly prepares to show Lindo a mink coat Rich gifted her, hoping to elicit a positive reaction. But Lindo harshly criticizes the gift, reinforcing Waverly's feelings of inadequacy and disappointment. Through a vivid flashback, Waverly recalls her childhood chess experiences, which serve as a metaphor for her relationship with her mother—marked by competition, manipulation, and emotional withdrawal. After a conflict over her chess-playing, Waverly feels pushed into quitting the game altogether, a reflection of her struggle for independence and her desire to escape Lindo's shadow. The chapter further unfolds as Waverly attempts to navigate her cultural identity and the expectations set by her mother. She worries about Rich facing Lindo's scrutiny and critiques. Their first dinner together is a comedic disaster, with Rich making cultural faux pas. Each misstep leads Waverly to struggle with her mother’s sharp disapproval and the shadow of her expectations, elements that had previously strained her first marriage to Marvin. Later, when Waverly's anger culminates in a showdown with her mother, Lindo appears unexpectedly vulnerable and fragile. In a moment of clarity, Waverly realizes that her perception of her mother as a powerful queen of emotional chess has both blinded her and shielded her from the deeper, more tender connection that exists beneath Lindo's tough exterior. Though the chapter ends with the decision to postpone the wedding, it brings a sense of hope. Waverly envisions a trip to China with Rich and her mother, recognizing that their shared journey could bridge their differences. Lindo’s comments about travel highlight her desire to connect—even if it comes across as domineering—ultimately hinting at the possibility of reconciliation and understanding between mother and daughter. This poignant exploration of cultural conflicts, generational divides, and the complexity of mother-daughter relationships makes the narrative both relatable and rich in emotion.

Chapter 12 | Rose Hsu Jordan: Without Wood

In Chapter 12 of "The Joy Luck Club," Rose Hsu Jordan recounts her childhood memories and ongoing struggles with her relationship with her mother and her husband, Ted. As a child, Rose was deeply influenced by her mother’s superstitions, believing in the power of her words, which often seemed mystical and all-knowing. She remembers sleeping in a bed with her sisters, each assigned playful nicknames based on their quirks, revealing themes of familial closeness and the protective nature of her mother. Rose’s childhood fears manifest in her nightmares involving Old Mr. Chou, a figure who symbolizes her anxieties and the struggles of listening to her mother. The dreams detail her feelings of panic and confusion, particularly the fear that she doesn’t belong, as her mother insists she must be guided by her wisdom to grow strong. However, Rose grapples with this guidance, finally acknowledging that she often bends to the opinions of others rather than standing firm in her own beliefs. Fast forward thirty years, and amid her impending divorce from Ted, Rose confronts intense emotional turmoil. At a funeral for a family friend, she navigates uncomfortable conversations with her mother about weight, food, and her personal life. Her mother’s insistence on Rose listening and valuing her words clashes with Rose’s tumultuous feelings about her marriage and her self-worth. As she processes her thoughts with friends and a psychiatrist, Rose explores her heartbreak and feelings of betrayal, leading her to question her identity and the life she built alongside Ted. When divorce papers arrive with a check, instead of feeling empowered, Rose feels crushed, reflecting on how little Ted seems to understand her value. The stark contrast between her feelings for the house they shared and her emotional distance from Ted illustrates her internal struggle. The metaphors of gardens and growth become prominent, as Rose realizes the state of her life mirrors the neglected garden outside. Ultimately, a turning point occurs when, upon confronting Ted about the divorce, she discovers that his self-interest drives him to move on swiftly, so he can marry someone new. This revelation liberates Rose, giving her the courage to assert herself firmly by declaring her intent to stay in the house and asserting her worth. The chapter crescendos into a dream where her mother and Old Mr. Chou are nurturing the garden, suggesting that while she has felt lost and weeded down by her circumstances, she is ready to reclaim her own identity, nurtured by her roots and her family’s legacy. As she stands her ground with Ted, Rose begins to understand the power of her voice, revealing a central theme of reclaiming agency and the conflicting yet interwoven identities between heritage and self-definition.

Chapter 13 | Jing-Mei Woo: Best Quality

In Chapter 13 of "The Joy Luck Club," Jing-Mei Woo reflects on her late mother, who passed away shortly before her thirty-sixth birthday. After receiving a jade pendant as a symbol of her "life's importance" during a Chinese New Year dinner, Jing-Mei becomes consumed with its meaning, haunted by the loss of her mother and the desire to understand her legacy. The chapter opens with her wearing the pendant every day, pondering the diverse meanings behind its ornate carvings but realizing she can never know what her mother truly intended. She recalls a specific Chinese New Year celebration with her mother, detailing their trip to Chinatown to buy crabs—a tradition and source of pride for her mother. Jing-Mei vividly remembers her mother’s character, from her brisk manner and sharp opinions on tenants to her quirky culinary preferences. The interactions during the dinner are lively and filled with a mix of familiarity and tension, particularly between Jing-Mei and Waverly, another daughter of a family friend. Their competitive banter reveals the nuances of cultural expectations and personal insecurities. As the dinner unfolds, Jing-Mei feels humiliated when Waverly dismisses her hard work as a copywriter, which evokes an internal struggle about her identity and self-worth. Her mother, who remains perceptively silent amid the chaos, offers her love through her culinary efforts rather than words of affirmation. As the evening ends, Jing-Mei tries to process her feelings of shame and inadequacy, wishing for a connection that feels increasingly distant. In a poignant moment, Jing-Mei's mother shares her thoughts on the jade pendant, indicating that its value will deepen over time as Jing-Mei embraces her heritage. This metaphor extends to the acceptance of her mother's complexities and the recognition of her own identity. After her mother's passing, Jing-Mei finds herself in the kitchen, cooking a dish her father loves, channeling her mother’s spirit, all while dealing with lingering doubts and memories, including the one-eared cat that symbolizes the haunting presence of the past. The chapter concludes as Jing-Mei confronts the past and her connections to her family traditions, signaling a journey toward understanding her identity and the significance of her mother's love. Themes of generational relationships, cultural identity, and the complexity of familial love are woven throughout, as Jing-Mei navigates her feelings of loss and belonging in a world marked by Chinese traditions and her own American experiences.

Chapter 14 | An-Mei Hsu: Magpies

In Chapter 14 of "The Joy Luck Club," An-Mei Hsu reflects on her daughter’s struggles with her failing marriage, feeling the weight of generational pain and expectations as she draws parallels between her own past and her daughter’s present. An-Mei recalls her mother, who was shunned for becoming a concubine after her husband’s death, illustrating the harsh realities women faced in Chinese society. Through powerful memories, she describes meeting her mother for the first time as a child, taking in her sorrow and the stories that shaped their lives. The pivotal moment occurs when An-Mei's mother is about to leave her uncle’s house to return to Tientsin; she bravely invites An-Mei to join her, challenging the oppressive family dynamics personified by her uncle and aunt. This decision denotes a significant shift in An-Mei’s life, as she chooses to embrace her mother's uncertain future over the familiar but dark environment of her uncle’s house. As they travel to Tientsin, An-Mei grapples with her complicated feelings—caught between the promises of a richer life and the painful separation from her brother. Her mother, who strives toward a new life, tries to instill in An-Mei the idea that they can find joy despite their shared history of suffering. Yet, as they arrive, the complex social hierarchy of Wu Tsing’s household unfolds, where An-Mei’s mother’s status as a concubine becomes painfully evident. An-Mei’s mother tries to maintain a sense of agency despite her circumstances, but is deeply impacted by Wu Tsing’s new young concubine, Fifth Wife. As tensions rise and her mother’s frustration grows, An-Mei witnesses the heartbreaking cycle of abuse and suffering that defines their lives. An-Mei’s understanding of her mother’s past, revealed through conversations with the family maid, Yan Chang, reveals the intricate manipulations and sacrifices that bind them. Ultimately, the chapter culminates in tragedy as An-Mei’s mother chooses to end her life rather than continue living with the shame and pain inflicted by the household. An-Mei's profound grief leads her to recognize her mother’s strength, embracing the legacy of resilience imbued in her own identity. The narrative conveys a powerful message about the struggle for self-determination against societal expectations, exploring themes of generational trauma, female empowerment, and the harsh truths of cultural roles. In a symbolic conclusion, An-Mei recognizes the power of her voice and the importance of breaking free from silence. The vivid imagery of magpies feeding on tears underscores her desire to reclaim herself and reject the oppressive lineage of expectation, setting the stage for a new generational narrative in a changing world.

Chapter 15 | Ying-Ying St. Clair: Waiting Between the Trees

In Chapter 15 of "The Joy Luck Club," the character Ying-Ying St. Clair reflects on her life and the disconnection she feels with her daughter Lena. Living in Lena's new home, Ying-Ying finds herself in what she perceives as a cramped and unwelcoming guest bedroom. She quietly criticizes Lena's American lifestyle, viewing their cultural differences through the lens of her Chinese heritage. Despite her love for Lena, Ying-Ying feels a sense of distance, as if she watches her daughter's life from afar, yearning to pass on the wisdom of her own past to help her. As Ying-Ying recounts her youthful days in Wushi, she remembers her beauty and wild spirit, her family’s wealth, and her vanity, which ultimately led her to a disastrous marriage. The pivotal moment came during a wedding celebration where a drunken man, whom she later married, inadvertently marked the beginning of her troubled future. This man’s explosive laughter and the watermelon he cut open foreshadow a life where Ying-Ying would come to know pain and betrayal. Married young, she experienced initial love and admiration but soon faced heartache when her husband abandoned her for other women. Over time, her spirit was crushed, culminating in becoming a ghost of her former self, drifting through life without purpose. After years spent in a distant rural environment, Ying-Ying transformed herself and eventually moved to America, where she married Clifford St. Clair. Despite the love she had for her husband, she felt detached, like a ghost in her own life, and often reflected on her past sorrows—her lost beauty and the child she aborted in a moment of despair. Now, as she prepares to share her story with Lena, Ying-Ying acknowledges that she wants to instill in her daughter the spirit and strength she has lost, recognizing that Lena's life is devoid of the depth and understanding that comes from knowing one's heritage and struggles. Ying-Ying resolves to confront her painful memories, believing that through this, she can liberate Lena’s spirit as well. The chapter beautifully explores themes of motherhood, cultural identity, and the complexities of love and loss, highlighting the interplay between Ying-Ying’s tumultuous past and her hopes for her daughter’s future. As she waits for Lena to understand, the story captures the essence of generational disconnect, the weight of cultural expectations, and ultimately, the fierce bond between mother and daughter that transcends their differences.

Chapter 16 | Lindo Jong: Double Face

In Chapter 16 of "The Joy Luck Club," Lindo Jong reflects on her daughter Waverly's insecurities as they prepare for Waverly's second honeymoon in China. Waverly worries about blending in with the locals and being seen as Chinese, but Lindo reassures her that no matter what, her daughter will always be recognized as an outsider. This moment reveals their complex relationship, where Lindo feels she has failed to impart her Chinese heritage to Waverly, who has assimilated into American culture. As they visit a beauty parlor for Waverly's preparations, Lindo is acutely aware of her daughter's embarrassment about her appearance, which highlights the generational and cultural divide between them. Lindo feels pride in her heritage, yet shame for being perceived as old-fashioned in Waverly's eyes. The narrative then shifts to Lindo’s memories of her own childhood, where her mother imparted wisdom through fortune-telling based on Lindo's physical features. Her mother communicated how one’s face reflects character and destiny, intertwining Chinese cultural beliefs with the idea of looking beyond appearances. Lindo recounts her own journey to America, emphasizing her struggles and the stereotypes she faced as an immigrant. She humorously shares anecdotes about adapting to American life, including her initial misunderstandings and the vast differences in cultural practices regarding marriage and identity. With these recollections, Lindo reflects on the significance of her name and the rather stark contrast between her life in China and the life she built in America. Throughout the chapter, themes of identity, cultural heritage, and generational conflict emerge. Lindo grapples with her own sense of belonging while trying to understand Waverly’s disconnection from their Chinese roots. As Lindo observes their similarities in their physical appearance, she recognizes how their experiences have shaped them differently. In the end, both women struggle to find a balance between their Chinese and American identities, revealing the complexities of being caught between two cultures. Lindo’s poignant reflections on love, sacrifice, and the weight of expectations carry a powerful message about the immigrant experience and the desire for one's children to thrive in a new world, even if it means losing parts of their heritage along the way. As the chapter closes, the mother-daughter dynamic remains delicate yet rich, echoing the complexities of identity that resonate throughout the novel.

Chapter 17 | Jing-Mei Woo: A Pair of Tickets

In Chapter 17 of "The Joy Luck Club" by Amy Tan, we follow Jing-Mei Woo on her transformative journey back to China. As the train crosses the border into Shenzhen, Jing-Mei feels a profound connection to her Chinese heritage, which she had previously denied during her youth. Accompanying her is her father, Canning Woo, who is on his own emotional trip to reunite with an aunt he hasn’t seen since childhood. As they travel to Guangzhou, the sights evoke memories and emotions in both father and daughter. Canning is touched by nostalgia, shedding tears as he looks out at the landscape that once held his childhood. Jing-Mei, now thirty-six and reflecting on her mother's wishes, learns of her two half-sisters from her mother’s first marriage, whom her mother had to abandon during wartime chaos. This revelation about her sisters fills Jing-Mei with anxiety about their upcoming meeting, particularly since their mother has recently passed away. After receiving a letter from her sisters earlier, Jing-Mei learns that Auntie Lindo had written back on behalf of her deceased mother, falsely giving them hope that their mother would one day reunite with them. As Jing-Mei grapples with the burden of this deception, she imagines the emotions her sisters will feel upon learning about their mother’s death. On arriving in Guangzhou, emotions run high as Canning is reunited with his aunt, Aiyi. Their embrace showcases the depth of family ties, yet Jing-Mei is acutely aware that her arrival in Shanghai will be markedly different, filled with uncertainty as she prepares to meet her sisters. Throughout the chapter, the themes of identity, the impact of family legacies, and the connection to heritage resonate deeply. As she navigates the bustling environment, Jing-Mei reflects on her mother's struggles and the sacrifices she made. The contrast between her family's past in China and her American upbringing helps highlight the complexities of her identity. As Jing-Mei finally comes face to face with her half-sisters at the airport, she moves through a whirlwind of mixed emotions—anticipation, fear of rejection, and recognition of shared lineage. Their reunion illuminates the bond they share, despite the absence of their mother, illustrating the enduring nature of family ties and the timeless wish to connect with one’s roots. The chapter closes on a poignant note, revealing that beneath their different experiences, they embody their mother's legacy and hopes, rediscovering what it means to be a part of each other’s lives.